On July 12, 2024, Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 (the “AI Act”) was published in the EU’s Official Journal. This means that the AI Act enters into force on August 1, 2024.

The AI Act is a comprehensive piece of legislation that sets out harmonised rules for the development, placing on the market, putting into service and use of AI systems in the EU. It imposes obligations and responsibilities on various public and private actors involved in the life cycle of AI systems, such as providers, users, distributors, and manufacturers.

Many organisations still seem to believe that they are exempt from the AI Act because they are not developing or placing AI tools and/or services on the market. These organisations fail to recognise that they are, or will be, responsible for the AI capabilities they are, or will be, using in the EU. Put simply, under the AI Act, a “deployer” is a person or organisation that uses an AI system, unless the AI system is used in the course of a personal, non-professional activity. As a result, most organisations that use AI will be considered “deployers” under the AI Act. As such, they may be subject to a number of regulatory requirements.

The various obligations set forth in the AI Act will become applicable at different times, contingent upon the nature and scope of the AI system or practice in question. The majority of the obligations will come into effect two years after the AI Act comes into force (August 2026). This encompasses a considerable number of the obligations imposed on high-risk AI systems. Nevertheless, the regulations pertaining to high-risk AI integrated into regulated products (i.e., systems subject to product safety regulation) will take effect after a period of 36 months (August 2027). The governance rules and the general-purpose AI regime will come into effect 12 months hence (August 2025). The prohibition on certain categories of banned AI and the general rules will come into effect six months after the AI Act comes into force (February 2025). Furthermore, the AI Act establishes specific timeline exceptions for certain systems that were introduced to the market or put into service prior to the Act’s enactment. For example, providers of general-purpose AI models that were placed on the market prior to 12 months from the AI Act’s entry into force will have 36 months from the date of entry into force to comply (August 2027).

Organisations that fail to comply with the AI Act face significant risks, which may include legal, reputational and financial consequences. The most effective way to ensure that AI systems are prepared for the AI Act is to take action at an early stage. Below are eight key steps that organisations should take to mitigate their regulatory risks.

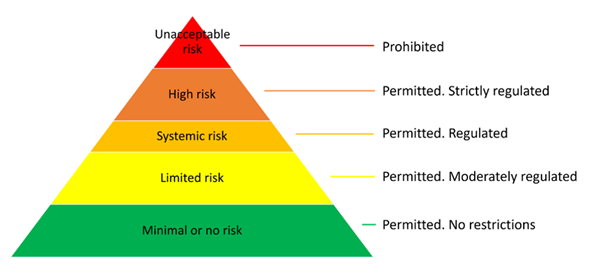

In essence, the finalised version of the AI Act is based on a risk-based approach that categorises AI systems into five levels of risk: unacceptable risk, high risk, systemic risk, limited risk, and minimal/no risk. So-called “general-purpose AI models” that pose no systemic risks arguably belong to the limited risk category.

Certain AI systems are exempt from the AI Act’s regulatory framework, such as those used exclusively for military, research, or personal non-professional activities.

AI practices that are considered to present an unacceptable risk, such as the use of emotion recognition systems in workplaces and educational settings, as well as the misuse of social scoring technologies, are prohibited. Prohibited practices contradict EU values and are unlikely to be widespread in Europe. However, it is likely that quite a few organisations are providing or using AI capabilities in one or more ways that involve high risk. Organisations that provide or use high-risk AI systems must comply with a set of strict requirements.

Accordingly, a critical first step for many organisations is to identify and catalogue AI-enabled capabilities in detail for subsequent risk assessment. Many organisations have numerous AI-enabled capabilities, some of which are custom-built, but most of which are integrated into various day-to-day platforms and are not immediately visible (e.g., AI driven solutions built into standard applications and SaaS offerings). Several studies suggest that it is not uncommon for organisations to have hundreds of AI-enabled capabilities in place across their business. Cataloguing involves discovering and listing every AI-enabled system in the organisation, allowing it to be categorised into one or more of the risk levels defined in the AI Act.

Cataloguing requires, among other things, a basic understanding of which systems are considered “AI systems” under the AI Act. The AI Act’s definition of an “AI system” is based on key characteristics that distinguish AI systems from simpler traditional software systems or programming approaches. The AI Act does not cover systems that are based on the rules defined solely by natural persons to automatically execute operations. Thus, an “AI system” is defined as “a machine-based system that is designed to operate with varying levels of autonomy and that may exhibit adaptiveness after deployment, and that, for explicit or implicit objectives, infers, from the input it receives, how to generate outputs such as predictions, content, recommendations, or decisions that can influence physical or virtual environments”. The key elements are “autonomy” and “infers”.

It is also important to note that all risk levels are not mutually exclusive. For example, an AI system that poses a systemic risk could also be considered a high-risk AI system, depending on the purpose for which the system is being used.

Before delving into the detailed requirements and necessary policy, practice, and contract changes, organisations need to determine which AI systems are classified as high-risk. The AI Act classifies AI systems as high-risk through three main criteria:

Sometimes an AI system itself can be considered as a product. If such a product is already regulated under certain EU legislation (as defined in Annex I to the AI Act), it will be considered high risk if it requires a third party conformity assessment before being placed on the market or used in the EU. Examples include medical devices, industrial machinery, toys, aircraft, and cars.

AI systems used as safety components for products also fall under high-risk classification if these products are regulated under certain EU legislation (defined in Annex I to the AI Act) requiring a third party conformity assessment before market introduction or use in the EU. This applies to AI systems in products like medical devices, industrial machinery, rail infrastructure, lifts, and appliances burning gaseous fuels.

AI systems are also considered high-risk if they match the descriptions listed in Annex III to the AI Act. These systems are considered to be potentially highly damaging and are used in areas such as biometrics, critical infrastructure, education, recruitment of personnel, access to essential services, law enforcement, immigration, and administration of justice and democratic processes.

AI systems shall not be considered high-risk if they do not pose a significant risk of significant harm to health, safety, or fundamental rights of natural persons, provided they meet specific criteria, like performing narrow procedural tasks or improving the results of previously completed human activities. However, AI systems used for profiling of natural persons are automatically classified as high-risk.

Once an organisation’s AI systems have been catalogued, the organisation should assess whether they meet the requirements applicable to each category. A thorough reading of the AI Act is essential to ensure that the organisation’s use of AI complies with the relevant obligations. The compliance assessment requires the organisation to identify, for example, its role(s) in the AI value chain as a provider, deployer, distributor, manufacturer, and/or importer. For high-risk AI systems, the rules include provisions on risk management systems, data quality, transparency, human oversight, accuracy, registration, quality management, monitoring, record-keeping and incident reporting.

A gap analysis can help organisations to avoid legal sanctions and reputational damage for non-compliance. Identifying and prioritising areas for improvement and adaptation allows organisations to focus their efforts on key compliance issues. A thorough gap analysis facilitates the detection of non-compliance issues and assesses how well an organisation’s current procedures align with the requirements of the AI Act.

Following the gap assessment, a customised compliance strategy should be formulated to address identified issues, including timelines, responsibilities, and resources needed. Specific actions and milestones should be defined for each compliance area, resulting in a detailed roadmap outlining the steps required. This strategy involves mapping AI-specific compliance procedures throughout the AI lifecycle and integrating them with existing IT processes. By allying compliance initiatives with existing structures, organisations can reduce disruption and ensure a supple transition to compliance with the AI Act.

Cross-departmental collaboration and a clear delineation of responsibilities, including both technical and legal roles, are essential to implementing the necessary changes and improvements for AI Act compliance. As a first step, organisations should revise their existing IT policies to align with the requirements of the AI Act. This includes creating or updating relevant codes of practice, outlining ethical principles and guidelines for the development and/or use of AI. For high-risk AI systems, the policies could cover risk management, data quality, transparency, human oversight, accuracy, registration, quality management, monitoring, record keeping and incident reporting. Organisations should also ensure that human reviewers are adequately trained and empowered to intervene in AI operations as necessary. These are just some examples of actionable tasks that can be initiated based on the results of the gap assessment.

Where possible and economically justifiable, some requirements that formally apply only to high-risk AI systems could be voluntarily applied to lower-risk AI systems. This will not only promote ethical and trustworthy AI practices in general, but also reduce the regulatory risks arising from potential misclassification of AI systems. Indeed, it may be difficult or very difficult to carry out a proper risk assessment of AI systems, for example in relation to fundamental rights. On the other hand, treating a system as high risk when there is no formal need for such a designation may be a source of unnecessary cost and complexity and may affect the likelihood of the system being developed, adapted, funded and/or used.

Organisations should strive to foster a culture of compliance and ethical use of AI. This includes providing adequate training and education to employees who are involved in or affected by AI systems, to ensure they have the necessary skills, knowledge and awareness to use AI systems safely and effectively. Relevant personnel should understand the AI Act and their role in ensuring compliance.

Where organisations have entered or will enter into contracts for the development, acquisition and/or deployment of AI-driven capabilities, they should ensure that the roles and responsibilities of each party are sufficiently specified and regulated to ensure compliance with the AI Act. Contracts should include provisions on liability and remedies for non-compliance or incidents. As a minimum, organisations should communicate and consult with partners and suppliers that provide or use AI systems or components to ensure that they are aware of and comply with the organisation’s AI policy and the requirements of the AI Act. Such interaction should also facilitate the exchange of information and feedback on the performance, risks and impacts of AI systems, and the identification and resolution of any issues or concerns.

Keeping abreast of any updates or changes to the AI Act and related legislation (such as the forthcoming AI Liability Directive) is necessary to ensure compliance. Organisations should be prepared to adapt policies and practices as new information or guidance becomes available. Participation in industry forums, working groups and discussions on AI regulation and best practice can help organisations keep abreast of the latest developments.

At over 140 pages (including recitals and annexes), the AI Act is a large piece of legislation, rivalling the scope of the GDPR. The AI Act encompasses a wide range of provisions and requirements, requiring a thorough understanding of specific definitions and interrelationships. The staggered application of the various chapters and provisions, ranging from six months to 36 months after entry into force, means that organisations may have to adhere to multiple compliance schedules, adding to the complexity. The provisions are subject to regular evaluation and review by the Commission and are therefore subject to change, requiring ongoing attention and adaptation by those affected. Organisations that fail to comply with the AI Act may be subject to significant administrative fines and other unfortunate consequences. For these reasons, it is strongly recommended that organisations work with legal and compliance professionals to ensure a thorough understanding and implementation of the requirements of the AI Act.

By taking the steps outlined above, organisations can not only ensure compliance with the AI Act, but also build a foundation for the responsible and ethical use of AI. Such a proactive approach will help mitigate risk, increase stakeholder trust and position the organisation for a sustainable, compliant and successful business in the evolving AI landscape.